The Prodigious Son: George Maciunas

Returns to Cooper in a New Exhibit

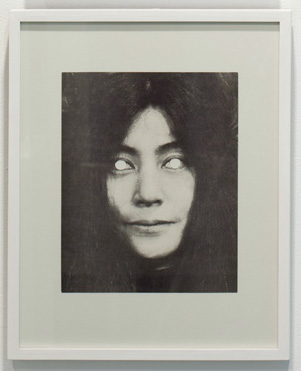

George Maciunas, Self-Portrait, 1961/2012

On Tuesday, December 11, the School of Art celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Fluxus movement with an exhibition of early works by its founder, George Maciunas (A’52) and a host of his frequent collaborators and colleagues. Anything Can Substitute Art: Maciunas in SoHo, exhibits a vast number of documents and works by Maciunas and other Fluxus protagonists spanning media from graphic design and film, to performance and bookmaking. The show has received numerous accolades. Holland Carter of the New York Times calls it “bracing” and writes, “anyone who wants to get a sense of how art can be both activist and existentialist will find bracing information here.” It has also been selected as an Artforum critic’s pick (requires login) and singled out for praise by ArtDaily.

Maciunas [pronounced ma-CHEW-nas] studied art, architecture, and design at Cooper Union from 1949 to 1952. “One could argue that a lot of his early orientations were formed here, so it’s exciting to present his work on the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of Fluxus,” Astrit Schmidt-Burkhardt, the exhibition curator, says. The bulk of the work on display arrives from The Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center in Vilnius, Lithuania, the country of Maciunas’ birth.

“When a major museum was being planned for Vilnius some years ago, Jonas Mekas and George Maciunas were quickly recognized as perhaps the most internationally influential artists of Lithuanian origin to emerge in the last century,” Kristijonas Kucinskas, Director of the Center, says. “Jonas Mekas was also a good friend of George Maciunas, and had acquired many works over the course of their friendship and collaborations in New York. So it’s great to bring the work from our collection back to New York, and back to Cooper Union.”

Named by Maciunas for its mercurial and uncontainable nature, Fluxus left its mark on everything from design and performance, to film and artistic research, and even the New York City real estate market, all of which are explored in the show. Maciunas and the other Fluxus artists often worked collaboratively and outside the art market. For Maciunas, Fluxus was about aspiring for a vision of art that was egalitarian and international, as exemplified in the provocative title of the show, Anything Can Substitute Art, taken from a manifesto he wrote in 1965. “This means that everything can be art, or that anything can be Fluxus—since Fluxus was intended by Maciunas to be a substitute for high art, in order to make it more available to everybody,” Schmidt-Burkhardt says.

In an effort to organize a deliberately shifting entity, the works have been divided into sections. Part one, “Genuine Places of Learning” presents early works, many of which make reference to European avant-gardes of the 1920s as well as centuries-old Chinese arts and crafts, mapping the coordinates and strategies for much of what Fluxus would come to mean, according to Schmidt-Burkhardt. “Mapping History,” the second section of the show, demonstrates the artist’s engagement with atlases, bookmaking, and other forms and vessels of knowledge in an attempt to critically re-think and reassess historical narratives as an immigrant working in New York.

While Marcel Duchamp elevated common objects like shovels and urinals to art through framing and context, Maciunas elaborated on this vision and argued that the framing and context, too, could and must operate as art. Thus graphic design and typography, as forms of packaging and delivery, played a major role in Fluxus and are explored in the show’s third section, “Designing Fluxus”. In Name Cards (1966), for example, we see Maciunas put his hand to designing radically divergent business cards for his friends and collaborates, each suggesting a different mood and affect: Claes Oldenburg gives off a Western, frontier vibe while Christo is presented in an urban construction cum proto-punk figuration. Displayed together, the cards become as compelling en masse, as a diverse artistic scene, as individually—much like the Fluxus artists they represent.

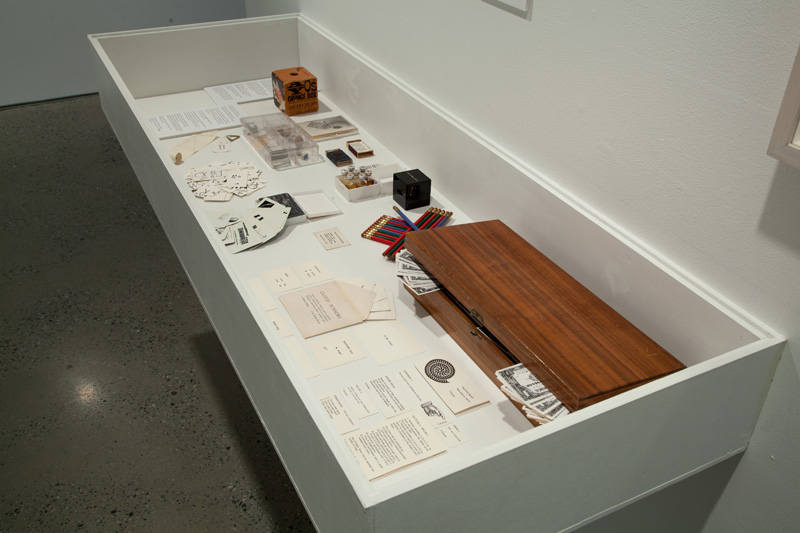

Two self-portraits by George Maciunas, collection of Fluxus objects, 1961 - 76; George Maciunas, [Die], 1973; George Maciunas,Yoko Ono Mask, 1970.

For many of these artists, anything that destabilized the traditional partitions of high art was celebrated, not least of all humor—a foundational component to the Fluxus approach. The “Substitute Art-Amusement” section of the exhibit explores this important dimension of the work, including Maciunas’ Die, an over-sized wooden sculpture of a lone playing die in which the artist inserted himself and allowed others to roll him around at a New Years eve party. Also included are various instructions and specifications for games, another genre for which the Fluxus artsits are well known.

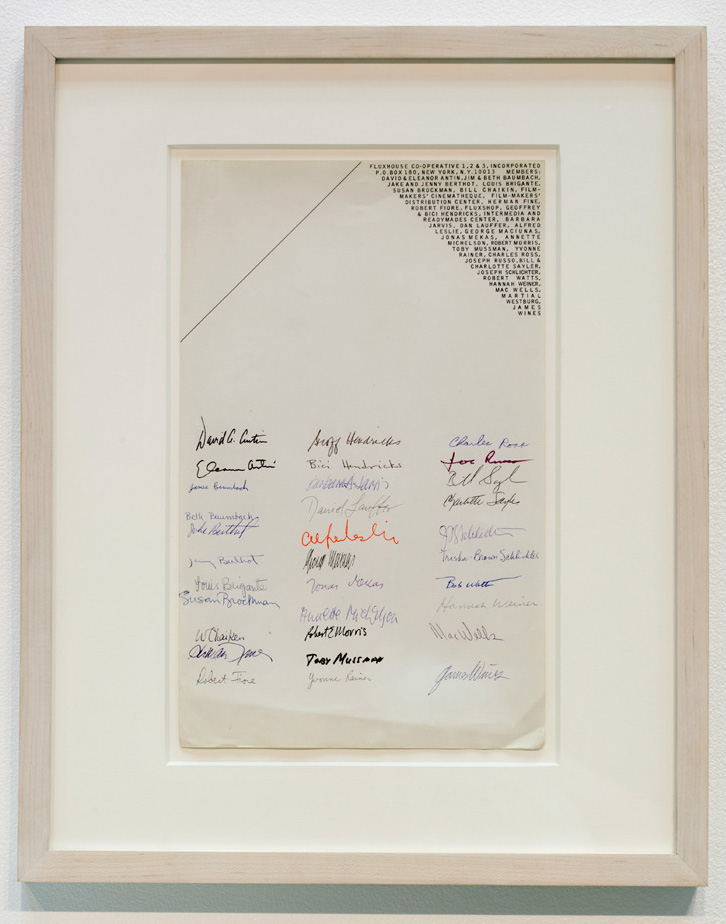

The full spectrum of Fluxus activities also includes business and cooperative initiatives, as explored in “Battle for Soho.” During the 60s, Maciunas helped create several “Fluxhouses” in Soho that acted as cooperatively owned and operated live-work spaces for artists in the then-dilapidated neighborhood. The documentation of his efforts—plans, writing, blueprints, contracts, and documentary photos—form the materials for this part of the show, an important note in the history of both Fluxus and Lower Manhattan. The final part of the exhibit, “Film Cultures,” focuses on the new media of the time, “something for which Maciunas and other Fluxus artists were incredibly enthusiastic,” Schmidt-Burkhardt says.

George Maciunas’ return to Cooper is significant, says Steven Lam, Associate Dean of the School of Art. “By deliberate curricular design, much of the School of Art has come to promote alternative modes of scholarship and research to conventional means of art-making,” Lam says. “Our students also seem to have an implicit coalitional consciousness which often leads them to form interesting collectives and ways of working together. I think Maciunas was without question a great social organizer, and very much a social artist in the spirit of the School of Art—he always thought within and also beyond the individual.”

Signature of 32 Fluxhouse Co-op members, on letterhead designed by George Maciunas (ca. 1967).