Exhibiting Fluxus:

Keeping Score in Tokyo 1955–1970:

A New Avant-Garde

Installation view of “Sogetsu Art Center and Fluxus” display in Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde at The Museum of Modern Art, November 19, 2012–February 25, 2013. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar

This is the first post in a new blog series entitled Exhibiting Fluxus, showcasing works from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift that are currently on view. Its predecessor, the Unpacking Fluxus series, gave the public an insider’s view of the physical and conceptual “unpacking” of this renowned collection, acquired by MoMA in 2008. The current series looks at ways in which these works are being integrated into new and dynamic contexts through the Museum’s cross-departmental collection displays and special exhibitions, reflecting the movement’s modus operandi of blurring boundaries between mediums and cultivating interdisciplinary dialogue and collaboration. Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde, currently on view on MoMA’s sixth floor, presents a number of Fluxus scores by avant-garde Japanese artists and composers. Scores are an essential component of MoMA’s Fluxus collection. Produced throughout the 1960s and 70s in the United States, Europe, and Japan, they take on a variety of forms from small event cards with text prompting the viewer to perform everyday actions to larger graphic scores with abstract compositions for indeterminate musical and dance performances. While these scores can be enacted, their producers considered them stand-alone art objects and often exhibited them in galleries to be experienced for their visual qualities, for example in Tokyo’s Minami Gallery, where the 1962 Exhibition of World Graphic Scores introduced works by Fluxus artists George Brecht, Dick Higgins, and La Monte Young to a Japanese audience.

Although works of various mediums on view in Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde had a conceptual impact on the Fluxus movement—from Gutai to Neo-Dada—this post is dedicated to one particular display of scores representing the activities of the city’s Sogetsu Art Center, which opened in 1958. The installation highlights five Fluxus-affiliated artists—Toshi Ichiyanagi, Shigeko Kubota, Yoko Ono, Mieko Shiomi, and Yasunao Tone—whose avant-garde and interdisciplinary performances helped establish the Sogetsu Art Center as a dynamic hub of international artistic experimentation and cross-cultural exchange in the first half of the 1960s. There are a variety of scores on view, which act as traces of the types of performances that unfolded on Sogetsu’s stage and operate as a window onto specific artists’ practices at this critical moment in Tokyo’s art scene.

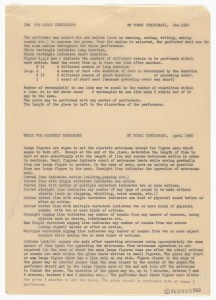

Toshi Ichiyanagi. IBM for Merce Cunningham and Music for Electric Metronome. 1960. Instructions. Master for the Fluxus Edition, typed and drawn by George Maciunas, New York. Typewriting on carbon, and stamped ink on transparentized paper, 11 5/8 x 8 3/16″ (29.5 x 20.8 cm). Unless otherwise noted, all works: The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift. Photo: Peter Butler

Toshi Ichiyanagi. IBM for Merce Cunningham. 1960 (Fluxus Edition announced 1963). Score. Master for the Fluxus Edition, typed and drawn by George Maciunas, New York. Ink, typewriting, and graphite on transparentized paper, 11 9/16 x 8 1/4″ (29.3 x 21 cm)

To the right of the display’s wall text hang two seminal graphic scores of avant-garde Fluxus composer Toshi Ichiyanagi: IBM for Merce Cunningham and Music for Electric Metronome. The scores—drawn and typed by Fluxus founder George Maciunas in 1960—are accompanied by a conceptual instruction sheet open to interpretation. The first score, IBM for Merce Cunningham, is a machine-like series of vertical, ink-drawn black and blank rectangles that signify to the performer the unfixed choreography and duration of actions and resting states. Avant-garde dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, who, like composer John Cage, introduced chance operations to his practice, performed at the Sogetsu Art Center with his dance company in November 1964. This event, in the context of the score’s flagrant homage to Cunningham, is evidence of the reciprocal flows of creativity and cultural admiration between New York and Tokyo at this time.

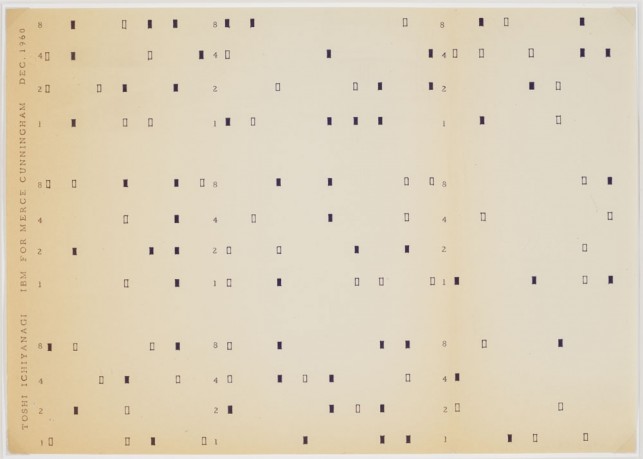

Toshi Ichiyanagi. Music for Electric Metronome. 1960 (Fluxus Edition announced 1963). Score. Master for the Fluxus Edition, typed and drawn by George Maciunas, New York. Ink and typewriting on transparentized paper, 11 3/16 x 15 3/16″ (28.4 x 38.5 cm)

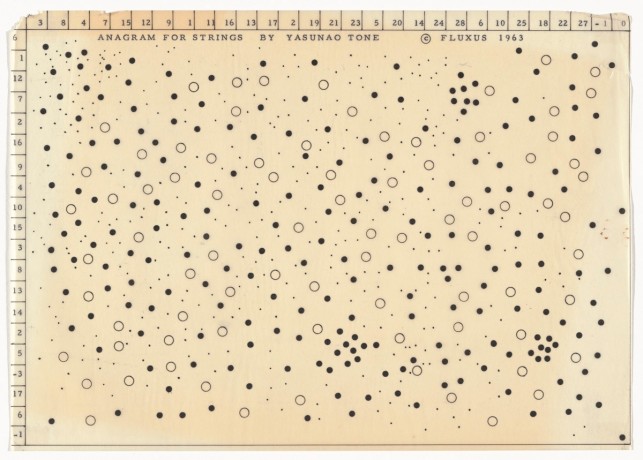

Analogous to IBM in its indeterminacy, Music for Electric Metronome is a divergent map of numbers that signifies to the performer how to configure and reconfigure the metrical ticks of a metronome. In the spirit of Fluxus, this work promotes the unconventional and improvisational use of an object—ironic in this case, since a metronome is a device typically used for keeping a fixed and steady tempo. Additionally, IBM and Music for Electric Metronome, like many Fluxus scores, give creative agency to the performers and allow them, in a sense, to re-write the piece in different iterations across various spaces and times. This aspect of the graphic scores is heightened by their inherent reproducibility; many were published and disseminated by Maciunas in 1963 as Fluxus editions, multiples stamped “© Fluxus” that could be purchased at low costs. An identical stamp marks Yasunao Tone’s adjacent graphic score Anagram for Strings, 1961—a constellation of filled and empty circles functioning as abstract notation for a string instrument of the performer’s choice.

Yasunao Tone. Anagram for Strings. 1961 (Fluxus Edition released 1963). Score. Master for the Fluxus Edition, typed and drawn by George Maciunas, New York. Ink and typewriting on transparentized paper, 8 1/4 x 11 11/16 (21 x 29.6 cm)

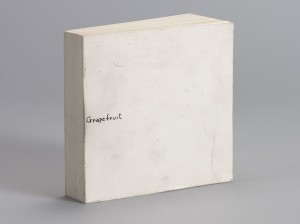

Yoko Ono, already a presence in the New York art scene by the early 1960s, traveled between the two cities to participate in experimental music performances at Sogetsu. Two copies of Ono’s Grapefruit, a book of scores and instructions divided into the categories of music, painting, event, poetry, and object, are exhibited in the vitrine below the graphic scores. Fitting the theme of the display, one copy of the book is opened to a score for an orchestra, instructing them to count all the stars in the sky for the duration of the piece, with a postscript that windows can be substituted for stars. When standing near the display, visitors can hear the looped sound of Ono coughing into a microphone (Cough Piece, 1961). The addition of an acoustic element to the display emphasizes the tension—pervading much of the Fluxus oeuvre—between the visual and the experiential.

Yoko Ono. Grapefruit. 1964. Artist’s book (Tokyo: Wunternaum Press). Offset on paper, 5 1/2 x 5 1/16″ (13.9 x 13.8 x 3.1 cm) (overall, closed)

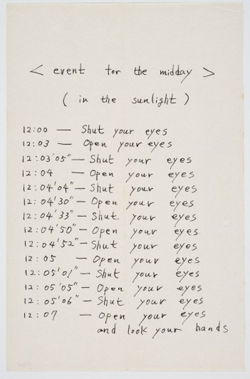

Complementing Ono’s Grapefruit are a number of small event cards by Mieko Shiomi that elicit the spectator to perform mundane tasks of the mind and body. Asking participants to open and shut their eyes seven times at varying intervals over the course of seven minutes and then to look at their hands, Event for the Midday (In the Sunlight) is emblematic of the mundane nature of these events. Shiomi’s scores resonate with George Brecht’s concept of the Event Score, which he originated during John Cage’s proto-Fluxus experimental composition course at New York’s New School for Social Research in the late 1950s. Although Cage too performed at Sogetsu, Shiomi developed her concept for the Event Score outside of his tutelage and unaware of Brecht’s concurrent activities. It would be Maciunas’s intervention that would cause these two parallel practices to intersect in Fluxus compilations like the anthologies and Fluxkits.

Mieko Shiomi. Event for the Midday (In the Sunlight). 1963. Event Score. Ink on paper, 4 9/16 x 7″ (11.5 x 17.8 cm)

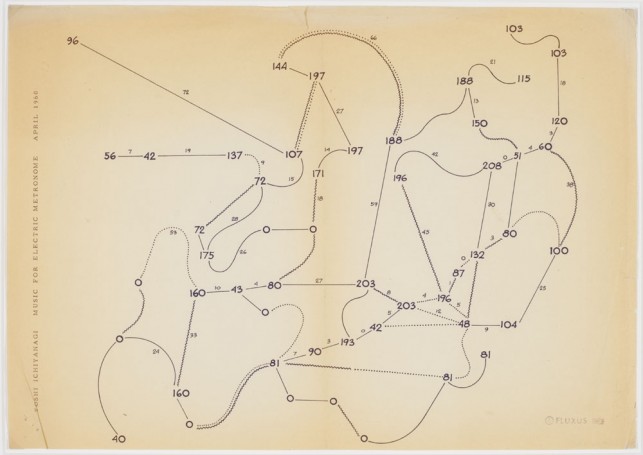

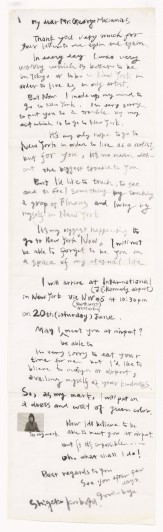

In the rightmost corner of the display hangs a conspicuous correspondence from Shigeko Kubota to Maciunas informing him of her decision to accept his invitation to join the Fluxus collective in New York in 1964. At first glance, this letter appears out of place in the context of the rest of the Fluxus scores, but as Kubota notes in her prose, this letter is staging what she considered the biggest performance of her life—leaving Tokyo to begin a new life in a foreign city. As this correspondence suggests, the dynamic programming at Sogetsu piqued Maciunas’s fascination with experimental Japanese artists and built bridges that conceptually and physically linked Fluxus artists across continents.

Shigeko Kubota. Letter to George Maciunas. 1964. Ink and collaged photograph on rice paper, 37 7/16 x 10 5/8″ (95 x 27 cm)