Studying Nomadism

Thomas Kellein

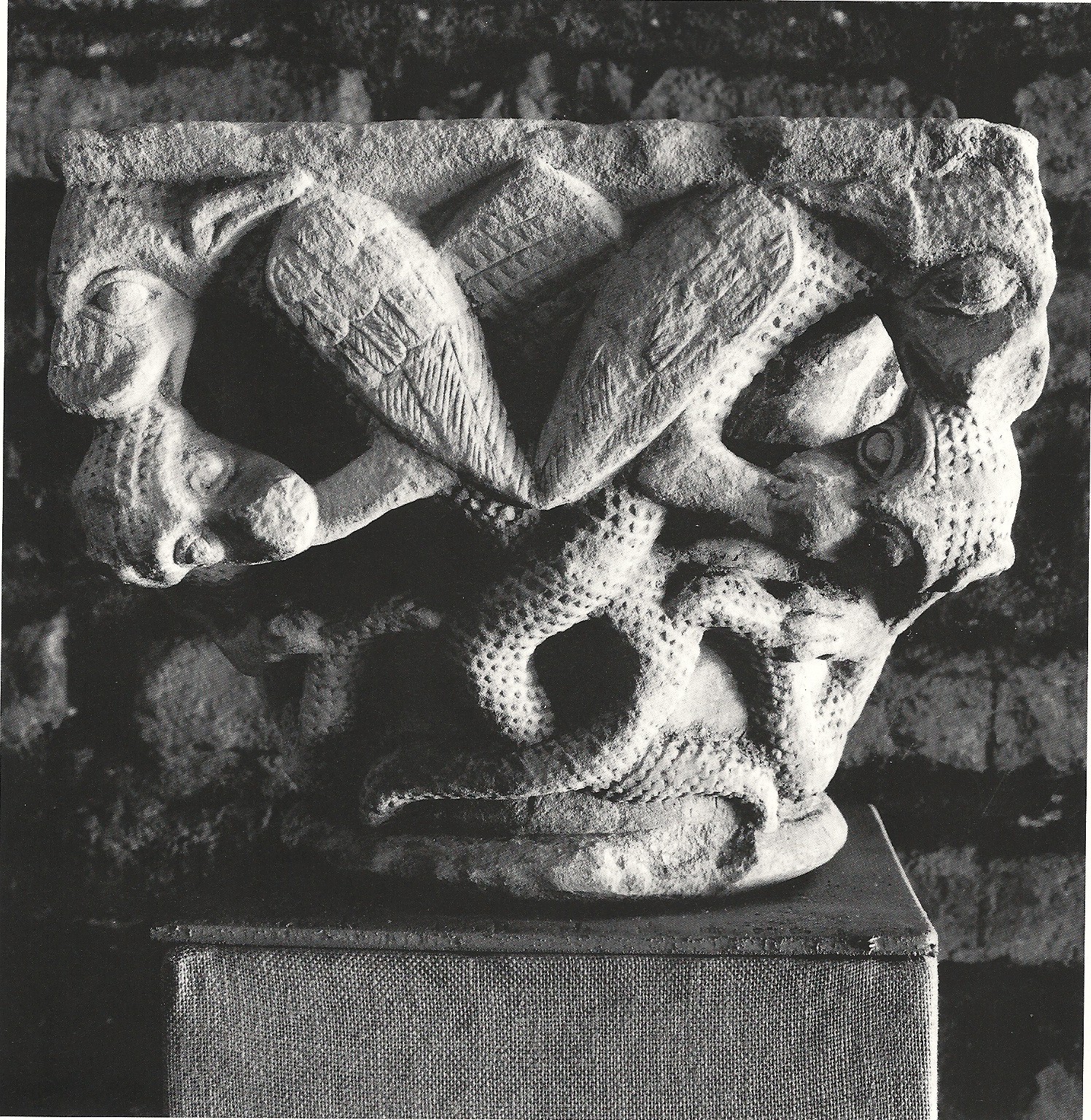

Maciunas' photograph of a Romanesque wal mosai, c. 1963

From 1949 to 1952, George studied art, graphic art, and architecture at Cooper Union in New York, and in 1953 completed a postgraduate degree. In 1952, he also enrolled at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh to study architecture with a minor in music. It was here that he first heard John Cage’s Music for Prepared Piano. (1) He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in architecture in 1955. In 1956, he returned to his mother after she moved from the house in Queens to an apartment in Manhattan. At first they lived in 86th Street, before taking an apartment at 550 Fifth Avenue. Mother and son now regularly attended concerts, as Aleksandras and Leokadia had done before the war in Kaunas. His sister remembers that in those days the idea was that George’s future wife should be a ballerina, like his mother. Meanwhile his mother, who would dearly have loved to have seen her son married, was highly critical of any steps he took in that direction. Any young woman who was a potential wife had to show great care in the way she handle things. Mother and son were almost obsessively tidy. As Leokadia later wrote, her husband had always insisted on honesty, punctuality, and domestic discipline.

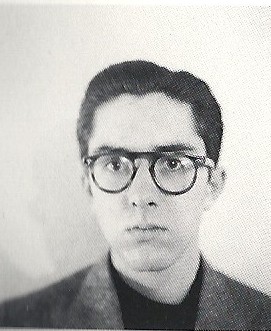

George Maciunas as a student, 1952

After graduating as an architect, George decided that his new dream job would be as a professor of art history. To this end he enrolled at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, He records in his biography of 1976 that until 1959 he attended evening lectures on the art produced during the great migrations of European and Asiatic peoples. With a scarcely imaginable titles of reference works on the history of Asiatic and Eastern European peoples that connected the pre-Christian migrations with the early painted decorations on porcelain. He was also interested in the origins of Asiatic cultures in the Bronze Age. He made meticulous drawings of geometric patterns and finely decorated weapons, and sketched maps to go with particular archaeological finds. He summarized passages from Ernst E. Herzfeld’s Iran in the Ancient East(1941) and from the sixteen-volume standard work published by the Geological Society of America in 1951. In 1956, while he tried to set himself up, with his mother’s help, as an “import merchant” of ancient musical instruments, which he advertised on writing paper he designed himself, he was also systematically mounting photographs of masterpieces of early Chinese, Japanese, and Scythian art on cards and adding locations and dates. The lectures at New York University formed the basis of a life-long encyclopedic interest in art-historical data(2).

Besides his study of the great migrations and the ensuring cultural transformations, he also acquainted himself with the history of the world’s great myths. From his study of a book by Uno Holmberg, he made a note of the shamanistic customs of Finno-Ugric peoples.(3) He learned about Chinese symbols and, more particularly, bird deities from a number of books by Florance Waterbury(4). He read up on the eagle cult of the peoples of Siberia and the role of Wotan and Walkyrie figures in Saxony, Friesland, Franconia, and Scandinavia. And he was eaually well informed about myths in Iceland. In addition to this, he also made outline pencil drawings of individual animal motifs and pictures of antlers and bones, for instance, and how they could be transformed into decorations for items of furniture.

Maciunas' photograph of a Romanesque capital in the Burgundy, France, 1963

He was interested in the lives of nomadic peoples not only because he had spent his early years in Switzerland, though no choice of his owan, and had then traveled as the child of a Russian mother from Lithuania via Germany to the United States. He was also in search of a real interest, something that he could identify with and move forward with, Nomadic people’s lofty aims and anarchic impulses particularly impressed him. The Huns, he noted during a lecture on art and its connections with civilization, were the real nomads in 500 B.C.(4) He was especially fascinated by the “animal style” seen in their cultural output. From his reading of a seminal essay by J.G. Andersson, he made a list of the animals that usually featured in this connection-including horses, sheep, and game- and of the explanations of their origins in hunting. And he observed that the function of the decorated shield was not only to visibly demonstrate the huntsman’s role, but also to protect him. He underlined a passage on the naturalism of the art of the peoples who lived by hunting(5).

Besides the Huns, Maciunas was specifically interested in Tataric, Mongolian, and Turkish nomads. He made notes on the peoples of Central Asia: Uzbeks, Kyrgyzis, Karakalpaks, Mongolians, and Siberian Turks(7). In his notes on Caspian peoples, exclamation marks accompany the information that they had to migrate because they had become too populous owing to the success of their cultivation of the land. Elsewhere he noted that it was at the end of the Copper Age, in the Euro-Asiatic plains, that writing had been invented(8). In his notes on the Vikings, he carefully listed which towns had been attacked from rivers and which from sea ports. He also made note of all the names of Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish Viking museums, as though he intended to visit them all one day.

Against the backdrop of the oldest and most ancient cultures, he laid the foundations for an all but fraudulent inventory of his own. Recorded in capital letters on notepaper, with illustrative photographs, it began in the Neolithic era with “Susa Pottery,” “Aimal Style Migration,” and the earliest heraldic devices(9). Maciunas wanted to use this as the basis for a comprehensive understanding of the facts and images that distinguish Assyrian, Iranian, and Central Asian cultures. He filled dozens of card indexes recording developments in the history of the Scythians and the peoples of Turkestan and China.

Soon after he had graduated in architecture, in 1956, he turned his attention to the global history of art-with the aim of creating an inventory of all its motifs, genres, and styles(10). At the time no one could have guessed at the teleological implications of this for Fluxus. But the grand scale and the idea of the migration of whole peoples were now in position. Maciunas would take these forward into the future. Since enrolling in those evening classes, he had become fascinated by the function of art as a tool and historic artifact. And he saw this art against the backdrop of historic migrations that brought with them economic homelessness, the recurrent search for land, the emergence of new cultural signs regardless of existing styles, the invention of writing, and nomadic life as a mode of existence. At the Institute of Fine Arts in New York, he acquired knowledge that would serve him well in the future. Later on, in Fluxus publications, he occasionally introduced individual animal motifs from the Bronze Age-wolves’ heads that look like dragons, snakes and boas, tigers, and shamanistic symbols.

This scarcely imaginable multitude of index cards was not necessarily intended for immediate use. Over the years he continued to make notes and sketches and reorganized the system a number of times. The importance of these early art-historical findings to Maciunas is evident from the fact that in 1964/65 he transferred the contents of a large number of old notes to microfilm, and in 1977, just a year before his death, he applied for a grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to research the concept of the avant-garde. The system he had created with stupendous zeal was not intended merely as an inventory. Maciunas was working on a parallel universe.

Maciunas' photograph of a Romanesque capital in the Burgundy, France, 1963

-

(1) See “This Is George Maciunas Speaking About Fluxus History” 20 April 1978, typescript, 14 pages, with a two- page postscript by Jonas Mekas, p.2, Silverman, unnumbered.

(2) Research has been under way since 1982 into Maciunas’ marked interest in art-historical diagrams. See Barbara Moore, “George Maciunas. A Finger in Fluxus,” in Artforum, vol.21, October 1982, pp. 38-45; Thomas Kellen. “I make jokes! Fluxus Through the Eyes of ‘Chairman’ George Maciunas,” in idem, Fluxus (London 1995), pp. 7-26; Astrit Schmidt Burkhardt, Maciunas’ “Learning Machines”. From Art History to a Chronology of Fluxus (Berlin 2001); idem, “Fluxus im Fluss der Zeit,” in idem, Stammbaume der Kunst. Zur Genealogie der Avantgarde (Berlin 2005), pp.357-90.

(3) Uno Holmberg, “The Shaman Costume and its significance,” in Annales Universitatis Fennicae Aboensis, vol.1, no.2 (Turku 1922), Silverman, unnumbered.

(4) Florance Waterbury, Early Chinese Symbols and Literature Vestibes and Speculations (New York 1922); idem, Bird Deities in China (Ascona 1952), Silverman, unnumbered. Maciunas often cut out pictorial motifs in publishers’ brochures.

(5) Ellis Hovell Minns, The Art of the Northern Nomads(London 1942), Silverman, unnumbered.

(6) J.G.Andersson, “Hunting Magic in the Animal Style,” in The Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. Ostasiatiska samlingarna, Stockholm, Bulletin no.4, 1932, Silverman, unnumbered. Maciunas made a particular note of pp. 221-25, 285, and 299.

(7) Marie Antoinette Czaplicka, The Turks of Central Asia in history and at the present day, peoblem, and bibliographical material relating to the early Turks and the present Turks of Central Asia (Oxford 1918), partic. pp.30-108, Silverman, unnumbered.

(8) Arthur Upham Pope(ed.), A Survey of Persian Art, from Prehistoric Times to the Present(London and New York 1938), vol.1, pp.47-51, Silverman, Unnumbered.

(9) A book of fundamental importance to the picture catalogue was M. Rostovtzeff, The Animal Style in South Russia and China. Princeton Monographs in Art(Princeton 1929).

(10) After 1955 Allan Kaprow, Dan Flavin, and Donald Judd all sought out an education in art history after their initial art training. It may have been no more than curiosity, but the fact that individual artists were keen to deepen their understanding of culture may also be what set in motion the unmistakable elevation of New York to an art metropolis. For all three of the above-named artists, these studies led to their deliberate artistic “intervention” in the course of art history.