“Exercise” at Stendhal Gallery

Exercise is a means of training oneself to achieve mastery: over the body, in a skill, or in an intellectual pursuit. Exercise entails a repetition of something for the sake of learning from it, yet the ultimate goal of this repetition is usually to enable oneself to achieve something unique: being in the best shape for one’s own body, utilizing one’s skills to create something novel, using one’s sharpened intellect to think of thoughts yet unthought. Fluxus is exercise for the mind. By playing with preconceived epistemological categories and encouraging a DIY approach to understanding the world, Fluxus aims to condition us to develop our own theories of knowledge.

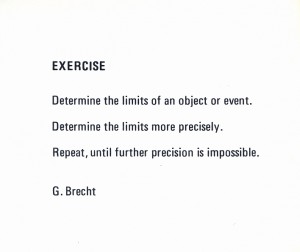

There is an aphoristic concision to most iconic Fluxus artworks. Yet rather than containing some perspicuous truth these works are often as elusive as zen riddles; they seem to cut to the very heart of the matter and to simultaneously raise questions about what that matter is. By confusing the categories we use to structure the sensory world, categories such as language, art, truth, and action, Fluxus can degrade the epistemological classifications enforced by a positivist primacy on logic and empiricism. Fluxus entreats us to see past these divisions, begs us to question how we may proceed in a manner that doesn’t result in reified concepts and the mind’s alienation from the body. Whether by turning awareness to objects and phenomena that often go unnoticed, or conflating music, performance, poetry, and mundane acts, Fluxus artworks beg us to question conceptual hierarchies. They encourage us to use our bodies and our brains to formulate new organizing principles with which to create new knowledge.

George Maciunas, founder of Fluxus, embodied this DIY approach to organizing information. He himself drew extensive historical and art historical diagrams on display in Contemporary Man, the latter situating Fluxus in a long lineage of artistic movements and developments. These diagrams not only distinguish between historical movements but isolate different categories such as common approaches to language and music that stretch across movements throughout time. Rather than rigidly periodizing Fluxus as an historical event, Exercise aims to look at what Fluxus achieves, in particular how it both embodies and encourages a novel way of thinking.

Like Maciunas’s charts connect strains in historical movements rather then simply depicting history as a procession of events, Exercise takes an unconventional approach to understanding Fluxus, finding the forebears of Fluxus attitude not simply in Dada or other avant-garde movements, but in entities as seemingly remote as classical philosophy and medieval logic. Whether it be fifth century Indian mathematicians who theorized of the concept of zero, pre-Socratic philosopher and believer in “universal flux” Heraclitus, fourteenth century philosopher and originator of the Ockham’s Razor principle William of Ockham, or eighteenth century English scholar of chance and probability Thomas Bayes, Exercise alleges that the Fluxus attitude long predates Fluxus, George Maciunas, or Duchamp.

The motif Exercise traces from these historical figures into the present day is the profound conceptual potential of concision. Like the punch-line or the haiku, Fluxus artworks often use short gestures to create a rupture in the fabric of understanding. On display in Exercise is an installation inspired by Maciunas’s charts that traces an intellectual history of this kind of profound brevity. Alongside this installation are Fluxus artworks by George Brecht, La Monte Young, Chieko Shiomi, Yoko Ono, and other artists who display this characteristic concision as well as respond to a directive to pursue one’s own epistemology. Juxtaposed with these works is artwork and conceptual exercises by David Bernstein, John Robert Moore, Nicole Demby, and Harry Stendhal inspired by Fluxus brevity as well as the notion that art can be a template for learning how to make ones own templates.

Author “Fluxus”

Essay by Nicole Demby

Contribution by Harry Stendhal