George Maciunas at Stendhal Gallery

The career of Lithuanian-born George Maciunas (1931-1978)- art historian, architect, designer, editor and founding member of the international Fluxus movement-happily defies categorization. Maciunas recognized that to be engaged with many different areas of endeavor is more amusing and, ultimately, more intellectually stimulating than to know a lot about just one thing. Between 1949 and 1960 alone, he studied fine and graphic art and architecture at Cooper Union in New York City, architecture and musicology at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh and the history of European migratory art at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts.

The career of Lithuanian-born George Maciunas (1931-1978)- art historian, architect, designer, editor and founding member of the international Fluxus movement-happily defies categorization. Maciunas recognized that to be engaged with many different areas of endeavor is more amusing and, ultimately, more intellectually stimulating than to know a lot about just one thing. Between 1949 and 1960 alone, he studied fine and graphic art and architecture at Cooper Union in New York City, architecture and musicology at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh and the history of European migratory art at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts.

The greater part of the exhibition at Stendhal focused on Maciunas’s diagrams and charts. Succinctly laying out various types of information pertaining to a given subject, he allowed previously overlooked and occasionally fanciful links to be established, and the whole to be more easily absorbed. Elsewhere, we could admire Maciunas’s experiments with typography, in which letters in different fonts and sizes are squeezed together and rotated, so that they read as abstract patterns before they divulge meaning. The rapid succession of patterns, single large numbers and letters in the silent black-and-white films produced in 1966 on clear film without the use of a camera also deconstruct meaning through processes of collage and displacement, achieving oddly mesmerizing, syncopated effects.

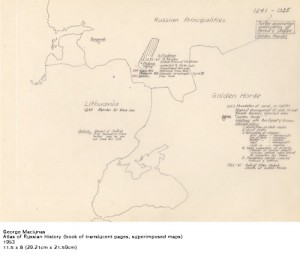

The charts and diagrams have a poetry all their own, with lines of information lovingly written out in careful longhand on delicate, now-yellowed supports and including more than a few misspellings. Atlas of Russian History (1953), in ink on translucent paper, comprises 36 sheets with meticulously traced maps supplemented by columns of handwritten information. The 38 charts in the European and Siberian Art of Migrations cycle(photo-collage, ink and pencil on paper), 1955-60, include small black-and-white photographs arranged in a gridlike fashion, balanced by written statements on the left and right. What makes these laborious projects compelling is that they continue to raise the question of what constitutes art more urgently than a great deal of later art using unorthodox materials, forms and strategies. In the wake of Duchamp’s notes for the Boîte-en-valise and in many cases years before Conceptualism, Maciunas implied that the artist can provide the connection between discrete bodies of knowledge. His charts look very much like the charts we find hanging in classrooms; artistic intention makes all the difference.

-Michaël Amy