Arts Magazine, September 1989.

By Bruce Altshuler

Fluxus Redux

Although it was one of the most energetic and wide-ranging elements of the art world of the 1960s, Fluxus has been given little attention in discussions of the period. In part this is due to the movement’s focus on events rather than on traditional visual artworks, and to the fact that what was made was largely mass-produced and quite inexpensive. Equally important is that Fluxus was funny, that many of its works are in some ways jokes or gags. In this, as in much else, Fluxus goes against the grain of the art world, and has paid the price in its consequent obscurity. But lately there has been renewed interest in Fluxus: the Museum of Modern Art Library recently exhibited some of the works; the most complete publication to date on Fluxus has just appeared; and other museum and gallery shows are planned have recently taken place.(1)

While it resists clear definition and demarcation, Fluxus is most widely viewed as the creation of George Maciunas, who through publication projects, concerts, events, and sheer energy orchestrated a diversity of creative impulses into an important force of avant-garde activity. This is the tack taken in the Museum of Modern Art exhibition, culled from the largest extant collection of Fluxus material, that of Gilbert and Lila Silverman of Detroit. It also determines the content of the new book, Fluxus Codex, product of long research by Jon Hendricks, curator of the Silverman Collection. The Hendricks-Silverman understanding of Fluxus is a purist one, specifying Fluxus as all and only that which is connected with Maciunas’s activities from his first use of the term in 1961, designating a planned publication, to his death from cancer in May 1978. Other material might be pre-Fluxus, post-Fluxus, or Fluxus-like, but it is not Fluxus.

Fluxus Codex is an elaborate and non-standard sort of catalogue raisonne. It seeks to list every Fluxus object-including all print publications, multiples, unique objects, environments, films, and ephemera, existing and non-existing-that is mentioned in either Maciuna’s publications or correspondence. No reference is made to the size or media of the objects, but every one of these citations is quoted. What we get is Maciunas and his correspondents (with the help of Jon Hendricks’s comments) defining Fluxus for us.

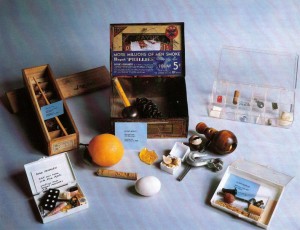

Here we find the irreverent, amusing, and occasionally aggressive expressions of the Fluxus sensibility: Takako Saito’s Sound Chess, in which the uniform cubic pieces are distinguished only by their making different sounds when shaken; Nam June Paik’s Prepared Toy Pianos; the photo-laminated table tops of Daniel Spoerri’s meals eaten by artists; Claes Oldenburg’s False Food Selection; Ben Vautier’s containers of dirty water; Ay-O’s mysterious Finger (or Tactile) Boxes, whose contents vary from vaseline and rice to razor blades and pins. There are the many plastic boxes with Maciunas-designed labels: Robert Filliou’s Fluxdust; Maciunas’s Excreta Fluxorum, with feces of various creatures; Bob Watts’s Fluxatlas, with pebbles from sites worldwide; George Brecht’s obscure game boxes; Geoff Hendricks’s Flux Reliquary; Ken Friedman’s Flux Clippings, some with toenail and others with newspaper clippings; Ben Vautier’s Fluxus Suicide Kit, complete with cord, bullet, and razor blade. Ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous, these works include Breton-like object-poems, spoofs on more serious conceptual art, and uninhibited bathroom humor.

The MoMA Library exhibition contains many such boxes, along with objects of other kinds: Joe Jones’s Violin in a Bird Cage, automatically played by a flapping rubber band; Emmett Williams’s poem abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz printed on a long scroll; George Brecht’s Water Yam event cards. In these pieces we see the heart of Fluxus, its relation to the growing “intermedia” activity of the late ’50s and ’60s. For Fluxus arose out of the world of experimental music, concrete poetry, Happenings, and new dance and performance.

The seminal figure here is John Cage, whose New School classes in experimental composition during the late ’50’s were attended by George Brecht, Allan Kaprow, Dick Higgins, AI Hanson, Jackson Mac Low, Philip Corner, and Richard Maxfield.(2) Cage’s own work was especially important for Fluxus and other artists in two ways. In opening music to ambient sound and to chance phenomena, he provided a primary model for the merging of art and real life toward which so many artists of the period aspired. And in the focusing of mental attention on which the success of his pieces depends, he reoriented art to the viewer as full participant in the creation of the work. Cage thus directed art both outward and inward, in each case making it something other than the personal expression of an individual artist. In Maciunas’s complex diagrams of the history of Fluxus, Cage occupied a central position.

It was at the New School in the fall of 1960, in Richard Maxfield’s extension of Cage’s class, that George Maciunas came upon this new sensibility. Here he met La Monte Young, recently arrived from California, who was organizing a series of performances in Yoko Ono’s loft on Chambers Street. Maciunas became involved with a large group of experimental artists, including Yoko Ono, Dick Higgins, Jackson Mac Low, Walter de Maria, Robert Morris, and Simone Forti. He established a similar concert and performance series at his own A/G Gallery, and began a career as avant-garde impresario.

Young also provided the occasion for Maciunas’s first publication project. He had assembled a collection of avant-garde material from artists in California, New York, Europe, and Japan for a special issue of Beatitude East. When the magazine failed, Young turned the project over to Maciunas, who designed and began the process of publishing a selection of this work-music, concrete poetry, event scores, essays-as the landmark compilation, An Anthology.(3) Taking on Young’s project gave Maciunas the idea for a magazine that would continue to present this sort of work, a publication he named Fluxus.

It was to promote his magazine that Maciunas organized the Fluxus festivals in Europe in 1962-63. The first Festum Fluxorum was held in September in Wiesbaden, where Maciunas was working as a freelance graphic designer for the U.S. Army.(4) From the wealth of material collected by La Monte Young he had scores for many events that would become the basic Fluxus repertoire. Maciunas assembled a group of expatriate artists working along advanced lines in Europe (Benjamin Patterson, Nam June Pailk, Emmett Williams), welcomed Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles from New York, and added Europeans as he extended his activities-Wolf Vostell, Addi Koepke, Tomas Schmit, Ben Vautier, Robert Filliou, Daniel Spoerri, Robin Page, and Eric Anderson. Fluxus festivals were held in Copenhagen, Amsterdam, the Hague, Paris, Dusseldorf (arranged by Joseph Beuys), Stockholm, London, and Nice.(5)

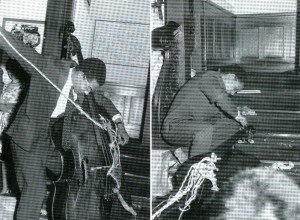

These “Fluxfests” encapsulate the essence of Fluxus-its humor, experimental spirit, provocation, and odd combination of silliness and seriousness. Central to the festivals were the “Fluxconcerts” in which fully planned events were performed in rapid sequence. Members of the orchestra might slide off their chairs at a signal from the conductor, or walk backwards over their instruments guided by hand mirrors. A violin solo might consist of the performer completely and carefully polishing his instrument” or a piano solo of the pianist driving a nail through every key. Members of the audience might be described in detail over a loudspeaker as they entered the theater, or be tied into their seats, or be led outside to the street and abandoned. There could be a performance of Joe Jones’s mechanical orchestra, or a symphony of street sounds from microphones suspended out the windows, or ten minutes of amplified telephone time signals or weather reports.

Although often associated with Happenings, Fluxus events were quite different. First, they tended to be relatively simple, best exemplified by George Brecht’s work of the late ’50’s and early ’60’s (published by Maciunas as Water Yam)(6). Generally constituted by a single occurrence, Fluxus events avoided the simultaneity that characterized Happenings. In this Fluxus is a cousin to Minimal Art, with none of the painterly, expressionist, or complex experiential aspects of Happenings. Fluxus events were more like one-liners. They disrupted normal expectations, opening the mind to whatever it might embrace-a striking image, a particular configuration of sound, a novel mental reflection. Fluxus also used the format of musical rather than theatrical performance. Fluxconcerts worked with event scores, Happenings had scripts. And while Happenings were primarily addressed to an audience, as in traditional theater, Fluxus events often seem directed as much to the experience of the participant as to that of the viewer. Paradigmatic here is Tomas Schmit’s Zyklus, in which the performer sits inside a circle of vessels all but one of which are filled with water, and pours consecutively and carefully from one to another until all the water evaporates or is spilled.

After Maciunas returned to New York in 1963, his publication projects proliferated. Fluxus magazine never appeared, but was transformed into the Fluxus Yearboxes, only the first of which (Fluxus I) was completed. Maciunas collected the materials from the artists, designed and produced the package and contents, and over the years assembled boxes on demand, with some variation in content (7). In 1963 he began producing Fluxus object multiples, in 1964 he turned George Brecht’s V Tre into an official Fluxus newspaper, and in 1965 he developed the largely two-dimensional Fluxus I into his version of Duchamp’ s Botte en Valise, the Fluxkit.

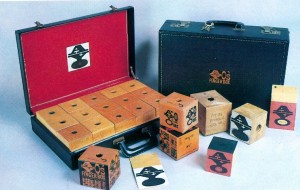

Although Fluxus publications were listed as works of individual artists, virtually all were realizations by Maciunas of others’ ideas. Like the Fluxus event scores, each admitting alternative ways of being performed, ideas for Fluxus objects allowed for numerous instantiations. The notion of “art by license” was in the air-one artist producing works for another. Spoerri even supplied certificates of authenticity for the “snare pictures” that he had Addi Koepke make for his 1962 Copenhagen show.(8) Maciunas applied this principle on a broad scale. He viewed Fluxus as a collective enterprise, anti-individualistic and antiprofessional, and felt free to fabricate multiples based on ideas casually mentioned, producing the objects according to his own interpretations. The look was pure Maciunas, with striking typography and layout (a graphic designer’s concrete poetry), often using the cheap plastic boxes readily found on Canal Street.(9)

Except for their strength of design, Fluxus objects do not offer much visually. Their interest lies in the ideas presented, and in the role that they playas a whole within the history of conceptual art. In this Fluxus differs from Nouveau Realisme, which was primarily a visual movement with important conceptual elements (most clearly seen in the work of Yves Klein).(l0) This is especially true when Fluxus objects are defined, as in Fluxus Codex, as essentially mass-producible by Maciunas. Certain artists did make important visual works during this period-in particular Spoerri, Filliou, and Brecht-but these were not distributed by Fluxus.

Maciunas’s background in design is significant for more than the appearance of the Fluxus publications. What he did was to package these ideas of the avant-garde in uniform containers, creating a line of goods. His ideal of mass-produced, non-precious, and inexpensive objects issued from a commercial as well as an ideological outlook. Of course, this had nothing ro do with profit-making. But while the Pop artists took the consumer culture as content, Maciunas embraced it as a form, marketing art as uniformly packaged and readily identifiable brand-name products. Compared with such rough unlimited multiples as Joseph Beuys’s Intuition (1968), Fluxus publications come to us looking more like consumer goods. In this cross-fertilization from popular design and advertising, Maciunas’s work looks forward to artists like Barbara Kruger, Keith Haring, and Jeff Koons, just as in typography and performance it looks back to Dada, Schwitters, and the Bauhaus.

In his desire ro package uniformly the ideas of diverse artists, Maciunas’s cultural and political radicalism coexisted with an authoritarian streak. Maciunas constantly attempted to designate who was and was not Fluxus, and he required the identification of particular works as Fluxus for “propaganda purposes” promoting the collective enterprise. A striking instance of this side of Maciunas was his picketing, along with Henry Flynt, the 1965 New York performance of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Originale, directed by Allen Kaprow and involving Fluxus artists. The consequent dissension within Fluxus was significant, and constituted a watershed in the group’s history.

Maciunas saw Fluxus as an anti-art movement, dissolving the distinction between art and ordinary life. In theoretical discussion he emphasized “concrete art,” unaltered objects or sounds or actions to which a special sort of attention is directed. Maciunas’s models here are Duchamp’s readymades and George Brecht’s events. A concentration on the “concrete” was intended to eliminate art by achieving its real purpose, the development of self-understanding and an enriched awareness of the world. Art exists in order to create particular mental states, not for the creation of precious objects. Maciunas’s view resonates with a characteristic American self-reliance-we have no need for artists, as anything can occasion aesthetic experience.

While Maciunas developed an ideology for Fluxus, treating it as a definite group complete with organizarional structure, few participating artists shared this view. His “manifestos” were not signed by others, unlike Pierre Restany’s 1960 Nouveau ReaIiste statement. Most Fluxus artists did a great deal of work unconnected with Maciunas projects, and there were activities and friendships with those excluded from his lists. Maciunas was jealous of other enterprises involving Fluxus artists-such as Charlotte Moorman’s New York Avant-Garde Festivals, Dick Higgins’s Something Else Press, and Wolf Vostell’s De-Collage-but these went on despite his opposition. Restricting Fluxus to Maciunas-related material, then, creates an arbitrary division within the work of many artists.

More importantly, to follow Maciunas in taking a narrow view of Fluxus is to limit our understanding of its significance. For much of the importance of Fluxus lies in its connections with the art of its time, both as influence and as concurrent expression; in the similarity between its reductive aesthetic and minimalism, or between event scores and process art as related varieties of conceptualism; in the widespread publishing of inexpensive multiples and artists’ books; in the profusion of body art, destruction art, and performance art. Fluxus essentially was expansive, tending to defy expectations and cross boundaries. And when Fluxus is fully situated in the complex cultural world of the ’60’s and ’70’s, it will be valued especially for, as Joseph Beuys remarked, “its provocative statement, (which) should not be underestimated; it addresses all spontaneous forces in the spectator that can lead to the irritating questions ‘What is this about?'”

-

1. Fluxus: Selections from the Gilbert and Lila SIlverman Collection, Museum of Modem Art Library, November 17, 1988–March 10, 1989, catalogue by Clive Phillpot and Jon Hendricks. The book is by Jon Hendricks: Fluxus Codex, introduction by Robert Pincus-Witten, (Abrams, 1988). The Whitney Museum exhibited the work of Yoko Ono, February 8-April 16, 1989. The Alternarive Museum presented Theater of the Object 1958-1972: Reconstructions, Re-crealions, Reconsiderations, May 6-June 24, while the Stux Gallery had Fluxus: Moment and Continuum, curared by Vik Muniz, May 10-June 3. In Paris, three galleries (Galerie 1900-2000, Galerie de Poche, and Galerie du Genie) featured Happenings & Fluxus Artists 1958- 1988 in June and July.

2. For personal accounts of these Cage classes, see Al Hanson, A Primer of Happenings and Space/Time Art (Something Else Press, 1965),92-102; and Dick Higgins, Postface/Jefferson’s Birthday (Somerhing Else Press, 1964),50–52.

3. See Fluxus Codex, 40. For a more detailed account of the labored beginnings of An Antholagy, see Jackson Mac Low in Rene Block, 1962 Wiesbaden Fluxus 1982 (Wiesbaden, 1983),114-119.

4. The U.S. Armed Forces played an important role in early Fluxus-in addition ro Maciunas’s employmenr, Emmett Williams was working in Darmsradt as a reporter for the daily milirary newspaper Stars and Stripes. Involved with a concrere poetry and performance group there, which included Daniel Spoerri and Claus Bremer, Williams gave the firsr published account of the European Fluxus fesrivals in that paper with an interview of Ben Patterson, August 30, 1962. See 1962 Wiesbaden Fluxus 1982, 81.

5. For the best Fluxus performance histories, see Harald Szeemann and Hanns Sohm, Fluxus & Happenings (Cologne, 1970), and Rene Block, 1962 Wiesbaden Fluxus 1982.

6. Most of George Brecht’s event scores were meant for use by individuals as directions for mental experiment and observation, and rarely for public performance. He was surprised to learn that many had been performed before large audiences at the European Fluxconcerts. For Brecht on his work and irs relation to Fluxus, see the interviews prinred in Henry Martin, An Introduction to George Brecht’s Book of the Tumbler on Fire (Milan: Multhipla Edizioni, 1978).

7. For a complete hisrory of Fluxus I, see Bamara Moore, Fluxus I, A History of the Edition (ReFLUXEditions, 1985).

8. See Daniel Spoerri, An Anecdoted Topography of Chance (Something Else Press, 1966), 182-183.

9. On Maciunas as graphic designer, see Barbara Moore, “George Maciunas: A Finger in Fluxus,” Artforum, Oerober 1972. The MoMA Library exhibition includes many of Maciunas’s mecharucals for Fluxus publications.

10. The relationship between Fluxus and Nouveau Realisme is an interesring one. Spoerri, of course, was an official member of both groups. Dufrene, like many Fluxpeople, was involved in concrete poetry and performance. In Fluxus 5: Western European Yearbook, Maciunas planned to include a piece by Pierre Restany on the “European garbage artisrs” as well as work by Niki de Saint·Phalle (Fluxus Codex, 118). Certainly when Maciunas arrived in France he found his path well-prepared by Nouveau Realisme.

11. G. Adriani, N. Konnertz, K. Thomas, Joseph Beuys: Life and Works (Barron’s, 1979), 98. On Beuys and Fluxus see 77-103. Long afrer participating in pieces at the 1963 Dusseldorf Fluxfest, and first performing the initial section of his Siberian Symphony there, Beuys continued to call his work Fluxus. Maciunas, however, excluded Beuys from Fluxus, considering him too egocentric and mysrical, and his work too baroque. Beuys himself felt that Fluxus lacked a program for personal development. But he credited Fluxus with expanding his conception of what sculpture could be, and following Maciunas’s death Beuys and Nam June Paik performed a memorial concert in Dusseldorf. For more on Beuys and Fluxus, see Caroline Tisdall, Joseph Beuys (Guggenheim Museum, 1979), 84-100,179-181.

Bruce Altsbuler writes on art philosophy and is Associate Director of the Zabriskie Gallery, New York.